- Home

- A J Waines

No Longer Safe Page 2

No Longer Safe Read online

Page 2

Eventually, the cabbie pulled up at the end of a track beside a broken wooden gate. He touched his cap as I handed over a couple of notes. He was keeping the change. Right. Fine.

He put the car into first gear and skidded away sending clumps of mud over my new boots; the ones mum didn’t approve of. Heels too high apparently. You’ll end up with bunions, she’d warned when I’d brought them home from a trendy shop near Sloane Square. In the old days, I’d have taken them straight back for a refund, but not now. I loved them; they made me feel elegant (which is difficult at five feet two) and they made me walk differently. Like a woman, not a child. Mum was grumpy for a while, but she didn’t say anything else.

I’d brought hiking boots to the mountains too, of course, but I wanted Karen’s first impression of me to be at my elegant best.

As I turned towards the cottage, I fought against the tugging wind. It was like being blasted by a fire extinguisher. I grappled with the toggles on my coat to force it to wrap across my body. My lovely shiny boots were being sucked down into squelchy sludge with every step. Then there was long grass, solid ground and several steps. Before I raised the knocker, I heard a key clunk into the lock on the other side.

Karen opened the door. ‘Alice – it’s really you!’

She swamped me in a hug that nearly swept me off the ground. The interminable journey, the savage weather was forgotten; I was home at last.

‘I’m so glad you could come – you can’t imagine,’ she said. ‘You look amazing!’ She looked down at the short denim skirt under my coat, my trendy boots. ‘Look at you – all feminine and gorgeous. Your hair is longer now – I love the shaggy fringe – my goodness, how grown up you look!’ My heart flipped.

She looked radiant. Her long golden hair was glossy – a field of corn in a midday sun – her skin tight with no blemishes in sight.

Before I could catch my breath, she’d reached down and humped my suitcase and backpack into the hall.

I couldn’t hide how moved I was; half a decade of sadness, hurt and grief at having lost her – and then the joy of finding her again – it was suddenly too much for me.

She gently stroked a tear away from my cheek. ‘It’s been such a long time,’ she said, fixing her gaze on me like I was the most important person in the world. As if she’d been waiting a lifetime for this moment. ‘Come and get warm. You must be frozen.’ She took my coat and gloves. She peeled off my boots as I clung on to the newel post and left them on the mat to dry. Then she led me by the hand through a door that resembled a wooden gate into the sitting room.

‘Look – isn’t this place adorable?’ she exclaimed.

The cottage certainly had ‘rustic charm’, with its quaint low beams decorated with horse brasses, a sturdy Welsh dresser in the corner displaying willow-pattern plates and a crackling log fire. I knew it wasn’t possible, but nevertheless it felt several degrees chillier inside than it did outside.

‘I managed to get the log fire up and running,’ she said.

Chunks of fresh firewood were hissing and spitting in the grate. I shivered and reached out towards the flames. ‘Listen – I made a terrible mistake,’ she confessed. ‘Total idiot, I thought there’d be central heating. But we can snuggle up in front of the fire. It’ll make things even more cosy.’

‘I’ll warm up in a minute,’ I said, slapping my cheeks. I knelt down on the hearthrug, the heat from the quivering flames making my skin tingle.

She clapped her hands together. ‘Right. Next big thing. Mel is in her highchair – you stay by the fire while I go and fetch her.’

Karen came back jiggling her daughter on one arm, pulling a little trolley with the other. Fastened to it was an oxygen tank, the size of a large bottle of Coke.

She didn’t give me time to react. ‘And here she is!’ she said, stroking her daughter’s earlobe. Melanie had a tiny plastic mask over her nose and mouth. ‘This is my wonderful friend from University – Alice,’ she said, adjusting the tubes away from her clawing fingers.

I took hold of her plump little hand. ‘She’s gorgeous.’ She had Karen’s alert silvery-blue eyes, but with darker, cropped hair the colour of mahogany, under a pink crocheted hat.

Karen tapped the oxygen tank. ‘She has to have this for the time being – about ten times a day – to make sure she’s breathing properly, don’t you, sweetheart...?’ Karen planted a kiss on the child’s cheek and kept her eyes shut, her forehead crumpling for a split second.

Melanie tried to pull the mask away from her face. ‘I know, darling – it’s very annoying, isn’t it?’ Karen looked up at me. ‘She’s still getting used to it. It’ll be fine.’

Karen’s voice was too light and airy; I could tell she was bluffing, making everything seem hunky-dory, but I wasn’t convinced at all.

‘I was so thrilled to hear from you,’ I said, not wanting to burst the bubble.

‘About time, eh?’ She tossed back her hair. ‘Anyway, I’m being a terrible hostess. I must get you a drink. What do you fancy?’ She didn’t wait for my reply and headed off into the kitchen. ‘Coffee with a splash of milk?’

She came to the doorway. ‘Still one sugar?’

‘Spot on.’

‘I’ve bought some prunes and sultanas, specially,’ she called out, as the door swung shut between us.

She’d remembered.

I cringed. I knew she’d had a penchant for After Eight mints and now wished I’d thought to bring some. Then I caught myself; Karen wasn’t the sort to have a favourite anything for very long.

I stood up to take a proper look around me and realised just how basic the place was. No double-glazing, no television or DVD player. The wallpaper was peeling away at the skirting boards and a sunken sofa stood limply in front of the fireplace. I didn’t dare touch the curtains, they looked like they might disintegrate, and the heavy musty smell reminded me of the crypt at Dad’s church.

The latch on the bare wooden door, more at home on a garden shed, clunked as I went through to join Karen. A smell of root vegetables and apples, slightly buttery, hit me. I had a look around: no washing machine, toaster or electric kettle.

Karen poured the hot drinks while I tried to look impressed by the chipped earthenware terrines, dented copper pots and antiquated stove.

‘We got here a couple of hours ago,’ she said, nudging me back towards the hearth with a mug. I pulled up a worn leather pouffe and huddled into it, my hands reaching for the flames between sips of coffee.

‘I’ve brought loads of jumpers you can borrow and there are spare blankets if you need them,’ she said. ‘I put a heater on in your room to take the edge off and there’s a hot-water bottle on your bed. Anything you need, just say. Okay?’

She sat Melanie on the sofa alongside a floppy blue rabbit that was wearing a mini version of her face mask – and disappeared for a moment. When she returned, she knelt beside me holding a pair of fingerless gloves. ‘I don’t know whether you brought any, but these are for you,’ she said, pressing them over my hands. They were made of Icelandic wool with a zigzag pattern on them. Exactly the kind I would have bought for myself if I’d been more on the ball. I grabbed her arm as she sat back on her heels.

‘You’re amazing. Thank you.’

As if on cue, Melanie clapped her hands together and squealed. She threw the rabbit on to the floor and Karen picked it up and made it dance. Melanie gurgled something along the lines of, ‘Blaba nowa mowa…’ and took a plastic block out of the bucket on the sofa and flung that on the floor, too.

Karen and I looked at each other and laughed. ‘She’s changed so much,’ she said, pressing her hand to her chest as if holding back a surge of loss and joy, all in one.

‘I’ve missed watching her grow.’ She pulled the hat down over Melanie’s ears.

She looked at me, then nipped her lips together and tipped her head to one side. ‘Oh, Alice – it’s been so long. I was useless at keeping in touch. I thought you’d have given up on me.’

<

br /> ‘No way,’ I whispered, barely able to speak.

‘We need to say a proper hello,’ she said, opening her arms. I let myself fall against her and she caught me, wrapping me up and holding on tight. It was awkward on the rug; we were in danger of toppling over, but I noticed her skin smelt the same and the lemon-honey scent of her hair was just as I’d remembered it.

‘I missed you,’ I whispered.

I wanted to tell her how desperately disappointed and upset I’d been when she’d failed to reply to my cards and emails, how hurt I’d felt when we’d drifted apart, but I didn’t want to moan.

She must have had her reasons.

I was certain it would all become clear during our stay. Besides, as the holiday unfolded, I wanted Karen to see how much I’d moved on and grown up. That’s where I wanted my focus to be, not on the way I’d felt so snubbed.

I cleared my throat. ‘What exactly is this place?’

‘It’s a crofter’s cottage.’ She got to her feet and pointed out of the window. ‘Glasgow is about ninety miles that way.’ She leant down and tossed another log onto the fire. ‘Sorry it’s not The Ritz.’ She pulled an impish face. ‘It was the only cottage the owner had left at short notice. She was about to give it a complete makeover.’

‘Ah…I’m sure it’ll be fine…it’s such a lovely idea.’

She picked Melanie up and adjusted the mask. ‘What shall we play with now Alice is here?’ Karen manoeuvred a box of toys towards me with her foot. ‘We’ve got everything in here,’ she said.

Melanie chose a wooden train, so the three of us took up positions on the floor and wheeled it back and forth. I had no experience with babies, only older kids, but Karen seemed completely in control and at ease. It didn’t surprise me. I don’t think I’d ever seen her flustered.

I looked from one to the other. ‘Can I take some pictures?’ I asked, thinking of the camera in my backpack.

Karen scrunched up her nose. ‘Not while she looks like this. Wait a few days and she won’t need the oxygen so much – then you can get some lovely shots.’

‘Of course.’

Melanie sat flapping her hands down onto the carpet. ‘Do you want to hold her?’ Karen carefully passed her over, hooking the tubes around my shoulder. The child bawled uncontrollably at the disruption, so I handed her straight back.

‘She’s tired,’ said Karen, kissing her cheek.

‘How long was she...? How long has she been ill?’

‘It’s been awful,’ she admitted. ‘Mel nearly died soon after she was born. She was at Great Ormond Street Hospital first, then they took her to the specialist unit in Glasgow after she developed problems with her breathing. She’s been in intensive care for months.’

‘I’m so sorry. You must have been desperately worried.’

‘It hasn’t been easy. I’m over the moon about bringing her home – well, here first for a bit, to make sure she’s okay – then finally home, to London.’

I went over to the tiny square window that looked out across the front garden. It was almost dark by now, but when I cupped my hands against the glass I could make out two bare apple trees near the centre and a cluster of bushes within a tumbling stone wall. It looked like the place had once been respectable, but it was now entirely overgrown.

‘The view from the track at the back is amazing,’ she said, blowing a raspberry into Melanie’s cheek and making her laugh. ‘There’s a loch nearby…oh…and a byre.’

‘A byre? What’s that?’

‘A sort of cowshed, by the look of it.’ She checked her watch. ‘Right – time for a bath, then bed for this little one.’

‘Can I help?’

‘Maybe next time. She’s not used to new people and don’t forget, I’m out of practice – I haven’t done this for a while.’ She laughed.

‘Of course – you’ve only just got her back.’

She put her arm round me. ‘I want you to be part of this, though. Why don’t you unpack? I’ll show you upstairs.’

The stairs were located inside the narrow chilly hallway and led to two bedrooms either side of a tiny bathroom, which had a freestanding bath on clawed feet, a loo and basin. There was no shower and an electrical water heater hung precariously on loose wires above the taps.

As I turned away from the bathroom, I noticed another set of stairs at the far end of the landing.

‘More rooms?’ I said.

‘Just one – a dormer attic conversion.’

She led me to my room. Like everywhere else in the cottage, it was quaint but basic. There was an old washstand on a dressing table, a wardrobe that didn’t appear to close and a scattering of rag rugs covering the threadbare carpet. The bedstead was the only piece out of context, with its bold and ostentatious black cast-iron frame topped with what looked like small cannon balls.

‘No one will bother us,’ said Karen, pulling my curtains closed for me. A small heater on the floor was rattling, but wasn’t making much difference to the air temperature.

I peeked inside Karen’s room. It was strewn with baby things: a changing mat, piles of nappies, sleepsuits, lotions, bottles – and there was a cot in the corner.

As Karen bathed Melanie, I hung up my gear, listening to the splashes and squeals. There was a clunk followed by the swoosh of water gurgling down the pipes, and shortly afterwards, I heard her footsteps pass my room and a door close. She came out humming to herself, swept into my room without knocking and flopped down on the bed.

‘She’s all sorted,’ she said. ‘I want you two to get to know each other.’ She sat up, smiling at me. ‘You’ll be changing her nappy before you know it.’

I bit my lip. This was Karen as I remembered her. She’d had her baby torn away from her for months – not knowing if she was going to live or die – and yet she was still keen to make me part of their intimate reunion.

Nevertheless, there was something about her that was trying a bit too hard. So far, our conversation sounded straight out of a woman’s magazine, where a celebrity invites cameras into her home and gives a trite interview to promote her new film. I wanted her to let down this ‘everything’s wonderful’ façade and tell me how things really were for her. I knew enough about hiding feelings to know something wasn’t right.

I shivered and she reached out her hand, inviting me to pull her to her feet. ‘Let’s get you warmed up,’ she said as she led me to the stairs.

‘I want to hear everything about you,’ I said, as we hunched up close to the fire. ‘The baby…and…’ I stopped short, realising I didn’t have a clue about what else she’d been up to over the last six years.

‘We’ll have all the time in the world for that,’ she said, rubbing my arm.

London life already felt like it belonged in my past – it was built of a tighter, rougher fabric, where everyone was happy to elbow you out of the way. Perhaps the back-to-basics living here would help me reconnect with simple things. I could stretch my legs and explore a new landscape, take photographs; I might even write some poetry. It would be like a retreat; a chance to get back in touch with myself again. Most of all, however, I wanted Karen to trust me, open up to me and stop treating me like a guest.

‘Let me show you the rest of the place,’ she said on cue, just as the warmth was starting to penetrate my outer layer.

It was like visiting a museum. Under the kitchen window was a small cream-coloured fridge and, further along, there was a low tap over a drain in the floor. In between, there appeared to be the one concession to modernity; a stainless-steel sink unit and draining board.

‘There’s a big chest freezer in the scullery,’ Karen said, pointing to a door in the corner. ‘I bought a few pieces of fresh meat from the village.’ She brushed a cobweb away from the draining rack. ‘We’ve got milk and butter – all the essentials to keep us going. The corner shop is three miles away.’

She swung open the fridge door and a cauliflower fell out with a thud onto the flagstone floor.

&

nbsp; ‘Crikey – there’s enough here for the whole winter,’ I said, taken aback. Each shelf was stuffed with packets, fruit, vegetables and jars. She shrugged, giving a clipped laugh.

We retreated to the comfort of the dancing fire again. The last of the daylight had been snuffed out and Karen switched on a lamp by the bookshelf. I couldn’t help thinking, with its distinct lack of modern appliances or home comforts, it bore rather too much of a resemblance to where I lived in Wandsworth. Palace Gardens – it sounded posh, but it wasn’t. It was a row of rundown terraced properties running alongside the grimy railway line.

I was twenty-seven and still lived with my parents. Dad worked as an undertaker and mum spent most mornings serving in a book shop. She was involved in local volunteer groups too, alternately fundraising for neglected animals, wild birds and humanitarian crises overseas.

Neither of them had grasped the concept of twenty-first century living; Mum still made her own clothes and Dad smoked a pipe. The most high-tech appliance we had in the house was a television, but they still seemed to prefer listening to the radio. Our home wouldn’t have looked out of place re-created at the Victoria & Albert Museum – to show what living in the tough 1940s was like.

Here, the tapestry fireguard, the broken grandfather clock, the rickety wooden clothes horse – were all embarrassingly familiar. Bare essentials instead of luxuries; it wasn’t going to be the least bit comfortable, but at least Karen was here.

I glanced over and her eyes had fallen shut; her belly rising and falling under her clasped hands. I watched her for a few moments, relishing her presence, not wanting to disturb her.

I always felt I’d let my parents down; at best I scraped average at everything – school work, baking, sewing – and for most things I didn’t even get as far as ‘average’. I tried hard; I just always seemed to be behind.

By the time I was about eight both Mum and Dad had lost interest in me, giving me menial tasks to do around the house to make up for the fact that I never excelled. One year they asked me to decorate our Christmas tree and I stood my masterpiece too close to the door, so when Dad came in the whole thing fell over, smashing baubles and sending pine needles everywhere. I can still hear the contempt in my mother’s voice when she told a neighbour about it: ‘She can’t even get that right.’

Dr Samantha Willerby Box Set

Dr Samantha Willerby Box Set Enemy At The Window

Enemy At The Window Lost in the Lake

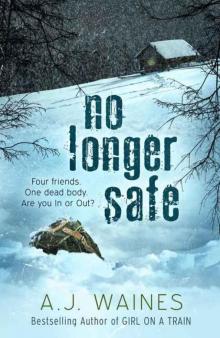

Lost in the Lake No Longer Safe

No Longer Safe![Inside the Whispers (Dr Samantha Willerby [Chilling Thriller] Series Book 1) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/inside_the_whispers_dr_samantha_willerby_chilling_thriller_series_book_1_preview.jpg) Inside the Whispers (Dr Samantha Willerby [Chilling Thriller] Series Book 1)

Inside the Whispers (Dr Samantha Willerby [Chilling Thriller] Series Book 1) The Evil Beneath

The Evil Beneath Don't You Dare

Don't You Dare